Developing ideas in writing does not come naturally to middle school students, but it is a skill that can be taught. I know this because of the books I’ve read and the fifty million essays I’ve graded during my teaching career. At the beginning of the school year, idea development is a common weakness I see, so I teach students how to develop their ideas, and I’m proud of the results.

Here are five strategies I use. The first two come from Joyce Armstrong Carroll’s Dr. JAC’s Guide to Writing with Depth; the final three are from Barry Lane’s After THE END. (I’ve read several books by these teacher writers, and they both offer fabulous resources.)

Developing Ideas in Writing with Prove Its

This activity is fun, easy to implement, and can be completed in one forty-five-minute period, so give it a try!

Teach

For this lesson, the students and I write together, with me projecting my writing onto the screen while students tell me what to write and copy our example in their writers’ notebooks. Sounds boring, but it isn’t!

What makes it engaging for students is the sentence we use: The witch is ugly. (It’s one of five Dr. JAC notes in her book, and students do have fun with it.) Our goal is to prove the witch is ugly by developing that idea, by showing instead of telling.

We begin by writing “The witch is ugly.” Students then offer sentences to prove the witch is ugly, working on transitioning from one sentence to the next by connecting their sentences to the ones that came before. This continues until we have a well-developed idea, until we prove it. When we have time, I follow this by having students draw what we wrote.

Student Examples of Developing Ideas in Writing with Prove Its

Here’s an example from a seventh-grade Pre-AP group:

The witch was ugly. She had a long, hollow face filled with warts. Her eyes were as big as baseballs but consisted only of pupils. However, one eye was missing, and a putrid green liquid was leaking through the hole where it had once been. She had long, black tangled hair, and in that mess were small bones from little children. She had a feeble body and all of her bones were sticking out, piercing through her yellowed skin. Even though she seemed menacing, there was no mistaking that she was only two foot four. But size didn’t matter, for she could eat a person alive in five seconds as seen by the bits of human flesh stuck in her teeth.

And here’s one from a regular-ed class:

The witch is ugly. She walks into the room with her big nose and smelly toes. Her green nose is as big as an elephant, and her toes smell like sour milk. Her face is old and saggy like a grandma’s stomach. She speaks, and her voice sounds like a cat choking on a dying bird. She looks like a deformed T-Rex with short, stubby arms. Also, she has a tail like a human centipede. Luckily, she doesn’t spot me hiding, and she turns, flaps her bat wings, and flies into the dark, stormy night.

Pretty good, huh? Of course, these are first drafts and still need a little revising, but you’ll notice the strong voices seen in both examples. This is what idea development can do to a piece of writing: move it from telling to showing, from humdrum to intriguing.

After completing this activity, students will understand prove-its and be ready to write one of their own.

Apply to Writing

Next, we’ll review declarative sentences (sentences that make statements). Students scan their drafts for these and highlight or underline ones similar to our witch-is-ugly example, ones that need proving. We then have a quick share to check their sentences and to give examples to those who may be having difficulties finding them.

Here are some from one of my classes:

- I was nervous.–Andrew

- It felt like forever.–Taylor

- The room had lots of decorations.–Courtney

- Paintball is dangerous.–Brian

- I saw a hermit crab.–Leah

- The water is cold.–German

- I was so excited.–Kaelani

- My grandma makes good food.–Ariel

They’ll then select one of those sentences to prove. They should choose one that is important to the story, one that would benefit from idea development. I like to have students write on large sticky notes (love the lined ones) so that they can attach these to their drafts at the spot they’ll add them.

I always allow students a few minutes to read their writings to elbow partners, small groups, and/or the entire class, depending on how much time we have. This builds community, and most students like to share what they write.

If students don’t have a draft to work with yet, then they can practice writing Prove Its with a declarative sentence that tells (e.g., my friend is rude).

Developing Ideas in Writing with CAFE SQuIDD

When I first started teaching, I came up with feed the cat, an acronym to help students remember various ways to develop their ideas. But Dr. JAC has a better one, CAFE SQuIDD, so I switched.

CAFE SQuIDD provides students with several ways to develop ideas (e.g., comparisons, anecdotes, facts, etc.). Plus, Carroll uses an excellent analogy, one that kids understand, that compares using these strategies to choosing items from a menu. When perusing a menu at a restaurant, we choose foods we like; we don’t order everything on the menu. CAFEE SQuIDD works the same. Students will use the strategies they prefer; they won’t use all of them in their writing.

Teach

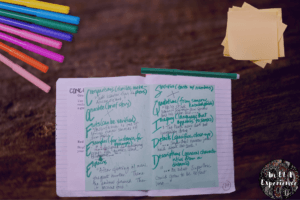

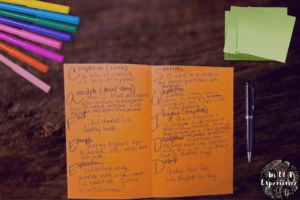

I introduce this by creating menus.

We fold a piece of colored paper in half hamburger style. (I use 8 ½ x 11” sheets so that they’ll fit into our writers’ notebooks.) On the front cover, we write “CAFEE SQuIDD: Idea Development Strategies by (student name).” (When our state added informational essays to our tests, I added an E for explaining.) They then illustrate the cover.

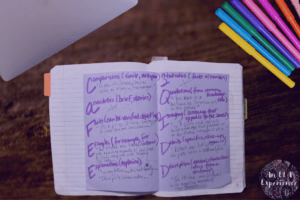

Next, we write C-A-F-E-E in large letters vertically next to the left side of the page and S-Qu-I-D-D vertically on the right side of the fold.

In smaller letters, we note what each letter stands for:

- C for comparison (comparison made with similes or metaphors, for example),

- A for anecdote (brief story that supports idea),

- F for fact (statement that can be verified),

- E for example (can begin with for example or for instance),

- E for explanation (when a topic is explained),

- S for Statistic (fact with numbers),

- Qu for quotation (quote from someone knowledgeable),

- I for imagery (language that appeals to the senses),

- D for detail (specifics), and

- D for description (general characteristic) or definition (a topic is defined). (I changed this to definition because the Common Core Standards specifically mention this.)

We then work together to find examples of these in fiction or nonfiction texts we’re studying. (When particular strategies are not used, we’ll write an X under that strategy.)

Here are a couple of examples from “Fish Cheeks” and “SuperCroc.”

If I need to reteach, we use chocolate and write original examples for each strategy.

Apply to Writing

After students have a good understanding of the idea development strategies from CAFEE SQuIDD, students reenter their writings, looking for places they need to develop their ideas and using some of these strategies to develop them. (I model this for them with my writing, moving through the acronym to see which strategy will work best.)

As usual, I allow a few minutes for sharing what they wrote.

Developing Ideas in Writing with Snapshots

A snapshot is Lane’s word for visual imagery, a common literary device used in writing that students will benefit from learning. When teaching this concept, I use the words snapshot and imagery, snapshot because it’s like a photo (easy to remember) and imagery because I want students to know the academic word.

Teach

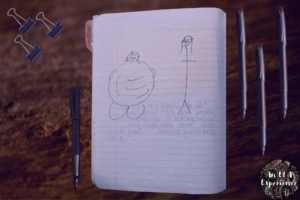

To introduce snapshots, I begin by asking students to draw a passage while I read it, and we use the example from James and the Giant Peach that Barry Lane provides in his book. Students then compare their drawings, noticing similarities, and we discuss how writers use visual imagery to create pictures with words.

I follow this by showing a few examples of snapshots from literature we read in class, like this one from “Dirk the Protector” by Gary Paulsen:

But when I rolled over I saw the dog.

It was the one that had been beneath the stairs. Brindled, patches of hair gone, one ear folded over and the other standing straight and notched from fighting. He didn’t seem to be any particular breed. Just big and rangy, right on the edge of ugly, though I would come to think of him as beautiful. He was Airedale crossed with hound crossed with alligator.

(I love the “. . . Airedale crossed with hound crossed with alligator.” What a great combination!)

Apply to Writing

Next, I have students find places in their writing where they can describe someone or something important and help readers see what they see. They’ll write their snapshots on bright sticky notes and attach them to the part of their writing that they will add it to later. They can also appeal to other senses as they write.

Sometimes, for a little writing practice, I’ll project a piece of art (or another interesting image onto the screen) and ask students to write a snapshot for it.

I then allow students to read their writings to their peers or the class.

Developing Ideas in Writing with Thoughtshots

Another technique writers use is telling readers what their characters are thinking. Lane calls these thoughtshots, and they pair excellently with snapshots.

Teach

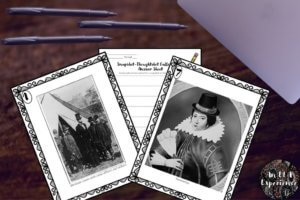

To teach thoughtshots, I begin with a gallery walk or a game of scoot where students look at historical pictures and write what the person may be thinking. (This can be done with snapshots too.)

For a gallery walk, I take students on a field trip into the hallway where I’ve taped the pictures a few feet apart. Working in small groups, students move through the stations and write what the character may have been thinking at the time.

I do the same thing with scoot, but for this activity, the pictures are taped to student desks and they work individually, moving every few minutes when I say, “Scoot.”

I also provide them with examples of thoughtshots from literature, like this one from Lois Lowry’s The Giver:

It was almost December, and Jonas was beginning to be frightened. No. Wrong, word, Jonas thought. Frightened meant that deep, sickening feeling of something terrible about to happen. . .

But there was a shudder of nervousness when he thought about it, about what might happen.

Apprehensive, Jonas decided. That’s what I am.

Apply to Writing

Again, with students writing on sticky notes or printed thought bubbles, I have them revisit their drafts and decide what the person or character was thinking at a particular moment in the story. They stick or tape these to that part of their composition and we read our thoughtshots to class members. (I found the pictured thought-bubble at Walmart.)

Developing Ideas with Explode a Moment

For this activity, I want students to find an important moment in the story and develop that idea fully, and one way to get that idea across is to show them a clip from a movie that is in slow motion.

Teach

I used to use a clip from Last of the Mohicans, but I recently noticed one that will grab students’ attention even more when I was watching the final battle in Season 4 of Stranger Things. We watch and discuss the clip, noting why slow motion was used for this particular scene. (Both clips are violent, so I do not use these with sixth graders.) I’ve also used these clips from Spiderman and Zootopia and had Barry Lane explain with his video.

Apply to Writing

Just as producers found a perfect time to use slow motion, students need to find a part of their writing where they need to slow down and explode the moment.

To help them find that moment, students can conference in small groups. After reading their drafts, group members can tell readers what they’d like to know more about. That will be a moment to explode.

Again, these can be written on sticky notes and stuck to the part of the story they developed.

Related Links

As always is my plan, I write so that you can implement these lessons without buying anything, but if you’d like my handouts, visit my TPT store for these developing ideas in writing activities.

For lesson ideas on revising for word choice, visit Blog #7: “Fun Activities for Synonyms to Inspire Students.”

“Developing Your Ideas” (college level)

Share Your Students’ Developed Ideas

Introduce your students to all of these revision strategies, so they can choose the one that works best for them.

I know you and your students will like Lane and Carroll’s strategies, but I still want to hear from you. Let me know which developing-ideas-in-writing activities you used and post a couple of student examples!