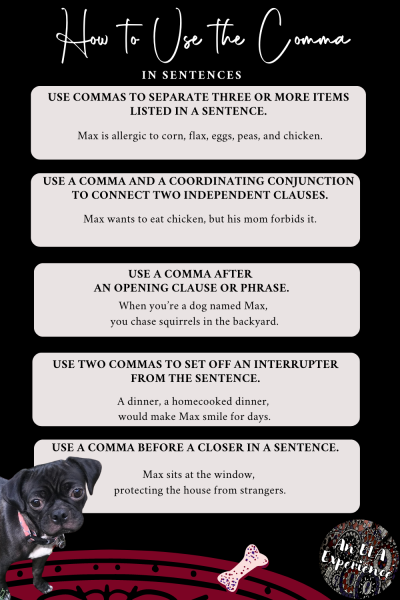

Students know how to use the comma with dates, numbers, and salutations when they enter middle school, but they don’t know how to use it in a sentence. (I bet you’ve noticed the same thing!) This is one reason I focus on five main comma rules–commas with items in a list, with compound sentences, with openers, with interrupters, and with closers. I’m providing you with DIY instructions here, but you’re invited to download my free comma rule lessons (including warm-ups, an introductory slideshow, and printables for anchor charts) to lessen your workload. (Just enter your name and email at the bottom of this page.)

More Reasons to Focus on These Rules

These comma rules allow students to

- review independent clauses (complete sentences),

- make connections as they see how various clauses (e.g., adjective and adverb) and phrases (e.g., appositive, prepositional, participial, absolute) can be used in the opening, interrupting, and/or closing positions of sentences,

- and move away from simple sentences and comma splices to more sophisticated sentence structures (e.g., compound, complex, compound-complex, cumulative).

Step One: Comma Anchor Charts (Hang These ASAP.)

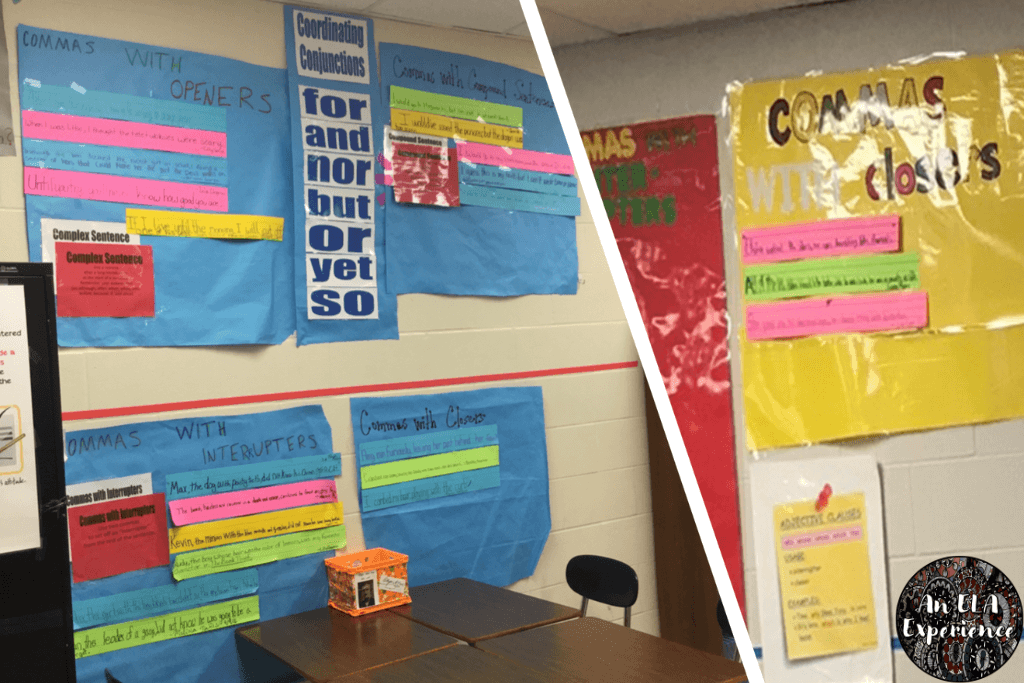

Anchor charts give students a resource to refer to as needed, and they’re especially helpful when learning comma rules. Begin by hanging them on your classroom walls. Add students’ stellar sentences to them as you teach each rule.

Here’s how you can get started with anchor charts for comma rules.

- Label five long pieces of butcher paper “Commas with Lists,” “Commas with Compound Sentences,” “Commas with Openers,” “Commas with Interrupters,” and “Commas with Closers.” Sometimes I’ve handwritten the labels; other times I’ve used the printed letters I have on hand (as seen in the above image). To save time, download the anchor chart printables (as seen in the image below) found with the “Free Comma Rule Lessons.” You can find them near the bottom of this page.

- Attach or write the rules and mnemonics, which we’ll discuss in step three, to or around the butcher paper with the corresponding rule.

- Draw stars next to students’ super sentences, the stellar examples, as they work or when you’re grading. (The comma rule booklet in step three offers a good place to start with this, and it’s also available in the download.)

- Train students to write their sentences on sentence strips (or directly on the butcher paper) whenever they see a star next to one of their sentences. (Be sure to check these for errors before they’re posted.)

- Teach students to refer to the anchor charts when writing by modeling. For example, say, “In a compound sentence, does the comma go before or after the coordinating conjunction? Let’s look at our chart.”

Step Two: What Do You Know About Commas?

Pose this question to students as an introduction to the following direct teach, and be prepared for some amusing responses (e.g., you use them in sentences). Also be ready to discuss some misconceptions (e.g., use them whenever you see the word and). One response you will hear is “use commas to separate things in a sentence,” and that’s why I start with that rule. It’s one they are familiar with.

Step Three: Direct Teach How to Use the Comma in Sentences

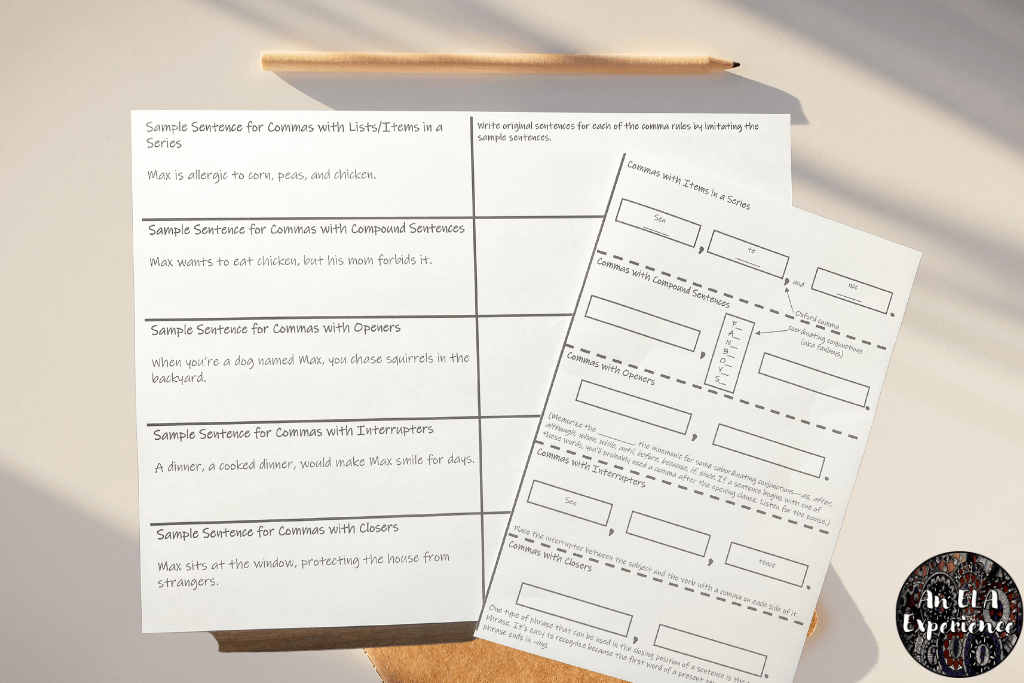

Students need plenty of practice to master comma use, so I begin with an overview of the five rules the very first week of school (not the first day). In a nutshell, I give them a foldable and walk them through each comma rule, modeling as we go, with the help of a slide show and document camera. Students can create their own by folding papers in halves (hamburger style) and drawing lines to create five sections.

Have students do the following for each rule:

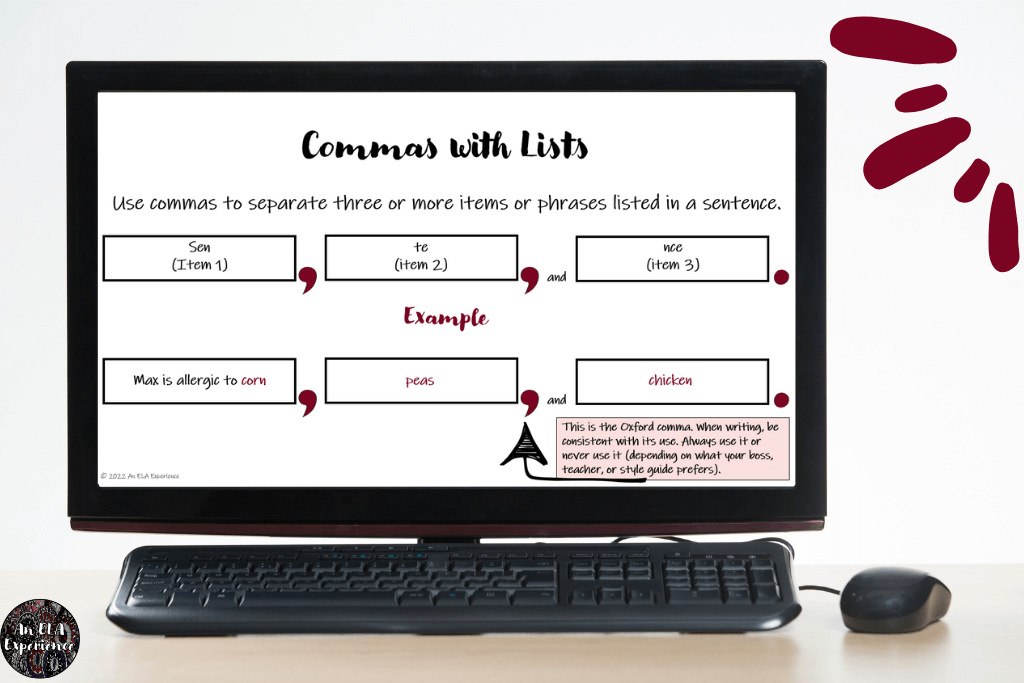

- Write the rule or draw a diagram (as seen in the above image).

- Write a mentor sentence that adheres to the rule.

- Imitate the mentor sentence to write an original sentence that follows the rule.

- Ask for volunteers to share their sentences with the class.

How to Use the Comma in a List of Items (AKA Commas with Items in a Series)

On the front page of the booklet, draw a diagram and/or write the rule along with your students: Use commas to separate three or more items or phrases listed in a sentence.

On the left inside flap, write a sentence for the students to copy that follows the rule. Mentor sentences from books you are reading in class offer great examples. I was reading Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat” when I found this one: “We had birds, goldfish, a fine dog, rabbits, a small monkey, and a cat.” I am a huge mentor sentence fan, but you can also write your own to grab students’ attention as I did with my slideshow (e.g., Max is allergic to corn, flax, eggs, peas, and chicken). (No, it’s not the best sentence I’ve ever written, but kids do like dogs, and it is a fun one to imitate. Plus, it’s also included in the comma rule download)

On the right inside flap, imitate the mentor sentence. For example, I’m allergic to cedar, long lines, and early mornings. Remember to model the imitation before asking students to imitate. They’ll understand concepts better when you show them what you expect. After students have finished writing their sentences, ask for two or three volunteers to share them with the class.

Oxford Comma or Not (A Note for Students)

Also use this time to discuss the final comma, the one before the and. It has three names–the Oxford, Harvard, and serial comma, so I’ll refer to it as the Oxford comma from this point forward to avoid confusion. Its use has been debated, but consistency is key. Always use it or never use it, depending on what your boss, teacher, or style guide prefers. I also let students know that our state won’t test them on it but that I prefer it. (See Khan Academy’s “Bonus: The Oxford Comma” for a quick video for students.)

How to Use the Comma with Compound Sentences

Next, move on to commas with compound sentences. Again, on the front page of the booklet, draw a diagram or write the rule: Use a comma when you join two (or more) independent clauses (complete sentences) with a coordinating conjunction.

On the left inside flap, students again copy a mentor sentence that follows the rule.

On the right inside flap, students imitate that sentence. Remember to model and allow for a volunteer share.

Examples of Coordinating Conjunctions (A Note for Students)

Use this time to discuss the mnemonic fanboys and have students note these conjunctions in their booklets: for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so. Students can use fanboys to memorize the coordinating conjunctions. If one of these words is being used to combine two or more sentences, then they’ll usually need a comma before it.

Simple vs. Compound Sentences (Another Note for Students)

When students are learning about commas, they tend to get what I call comma-happy, which is just a part of the process. However, they should know that a compound subject or compound predicate does not equal a compound sentence. If the sentence is not made up of two complete sentences, a comma is not needed.

For example, commas are not needed in these two sentences.

- Jay and I went to a concert.

- I walked to the garage and tripped on the treadmill.

How to Use the Comma with Introductory Clauses and Phrases

Again, draw a diagram or write the rule: Use a comma to set off an opener from the rest of the sentence.

Then, write a sentence for students to copy that follows that rule and have students imitate that sentence.

Examples of Subordinating Conjunctions (A Note for Students)

One type of opener is the adverb clause. It is a dependent clause (fragment), so it can be attached to an independent clause (sentence) to form what is called a complex sentence.

Adverb clauses begin with subordinating conjunctions. You can memorize some of the most commonly used subordinating conjunctions with the mnemonic aaawwubbis (as, after, although, when, while, until, before, because, if, since). If a sentence begins with one of these words, you will usually need a comma at the pause to set the opener off from the sentence.

It’s also interesting to note that this comma rule has been broken often enough to be labeled one of the most common errors in college essays. (See “Top 20 Errors in Undergraduate Writing” for more information on this statistic.)

Adverb clauses can act as interrupters and closers too, but a comma is not needed when they close a sentence. (These comma rules can get a little tricky!)

How to Use the Comma with Interrupters

Draw a diagram and/or write the rule: Use two commas to set an interrupter off from the rest of the sentence.

Next, write a sentence that follows that rule for students to copy and imitate.

Commas with Appositives (A Note for Students)

In the above example, an appositive phrase was used as an interrupter between the subject and the verb. An appositive phrase renames or defines a noun or pronoun, and these phrases often begin with a, an, or the. They can also act as openers and closers in sentences, but they should be next to the noun they are referring to.

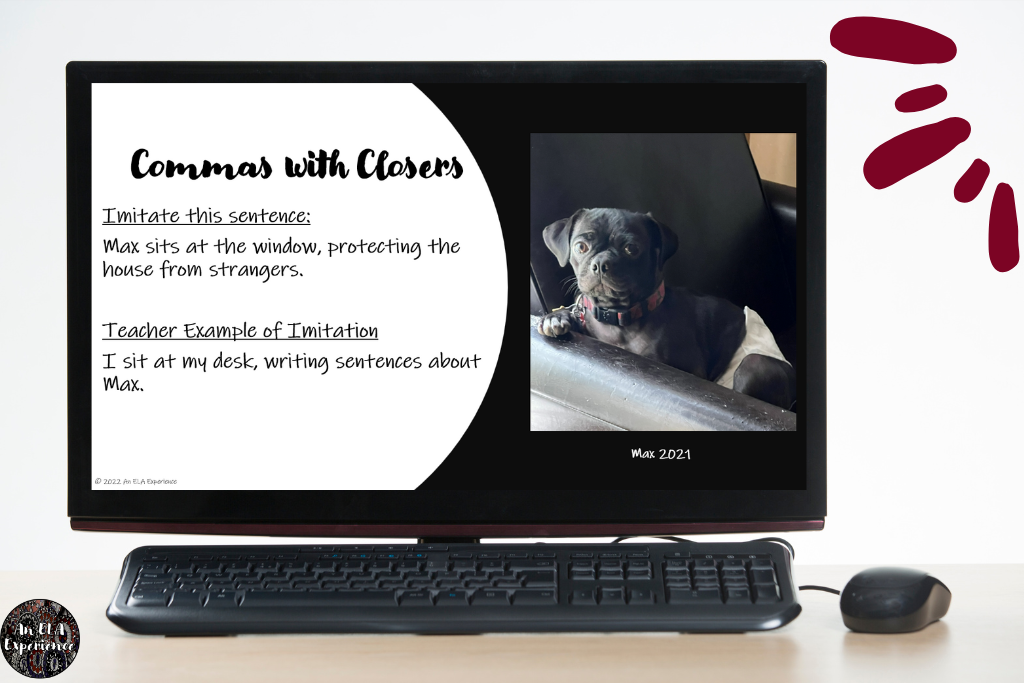

How to Use the Comma with Closers

On the front of the booklet, students draw a diagram or write the rule: Use a comma with a closer.

Once again, they write and imitate a mentor sentence.

Participial Phrase Examples (A Note for Students)

This example uses a participial phrase as a closer. Present participial phrases are easy to recognize because the first word of the sentence is a verb that ends in -ing, a participle (pretending in this example).

Dangling Participles (Another Note for Students)

Watch out for dangling participles. They occur when it’s unclear who or what is being modified. (I remember a state test where an incorrect option had a horse named Dudley surfing the internet.) Here’s an example of a dangling participle (of what not to do):

Max sits on my lap, writing sentences about dogs.

In this example, Max is the one writing sentences. (He’s a smart pup, but not that smart.) 😉

Step Four: Practice with Daily Warm-Ups

There is so much to cover in our ELA curriculum that many teachers skip the comma rules, but you can cover a lot of ground with a five-minute warm-up each day.

- Use interesting sentences from the texts you read in class as mentor sentences.

- In the beginning, find short sentences that adhere to the rule, and study one rule at a time. (While studying openers, interrupters, and closers, I focus on one clause or phrase for three weeks, showing students how to move it to various positions in the sentence.)

- Students write one sentence at the beginning of class. (Each week, start with combining sentences and then move to imitating and writing.)

- When students finish writing their sentences, ask a couple of them to share responses and have all of them make corrections to their sentences when needed.

- Finally, remember to draw stars next to the best sentences for your anchor charts.

Step Five–Apply to Writing

The more students write, the better they write, so have them write often. When they’re writing, ask them to include and underline a compound sentence, for example, or have them combine two short sentences to create one. When they’re editing, focus on checking comma use for the rule you’re studying.

Related Links

Excellent Compound Sentence Activities that Get Results (Blog #11)

Adverb Clauses and How to Teach Them to Teens (Blog #12)

“Teaching Students to Edit a Little Every Day” (Blog #9)

“When to Use a Comma: 10 Rules and Examples”

A Few Reminders on Teaching Commas

As you read this article, you may have noticed that keywords are great indicators for comma rules and grammar terms, so here’s a quick recap.

- Students can remember the coordinating conjunctions with the mnemonic fanboys (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so).

- They can memorize the aaawwubbis mnemonic to remember some commonly used subordinating conjunctions (as, after, although, when, while, until, before, because, if, since).

- Appositive phrases often begin with a, an, or the.

- The first word of a present participial phrase ends in -ing.

I hope you enjoyed getting to know Max and learned something new! Remember to sign up for my free comma rule resources for teaching students how to use the comma!

2 Responses

I love the practice sheet with the rectangular boxes!

Yea! I’m thrilled you like it! Thank you for commenting, Lasette!